How to Diversify a Concentrated Stock Position Without Losing Sleep (or Facing a Big Tax Bill)

Jonny Jonson is a financial advisor at Compound who specializes in helping tech professionals and high earners navigate complex financial decisions including career transitions, family planning, and major life changes.

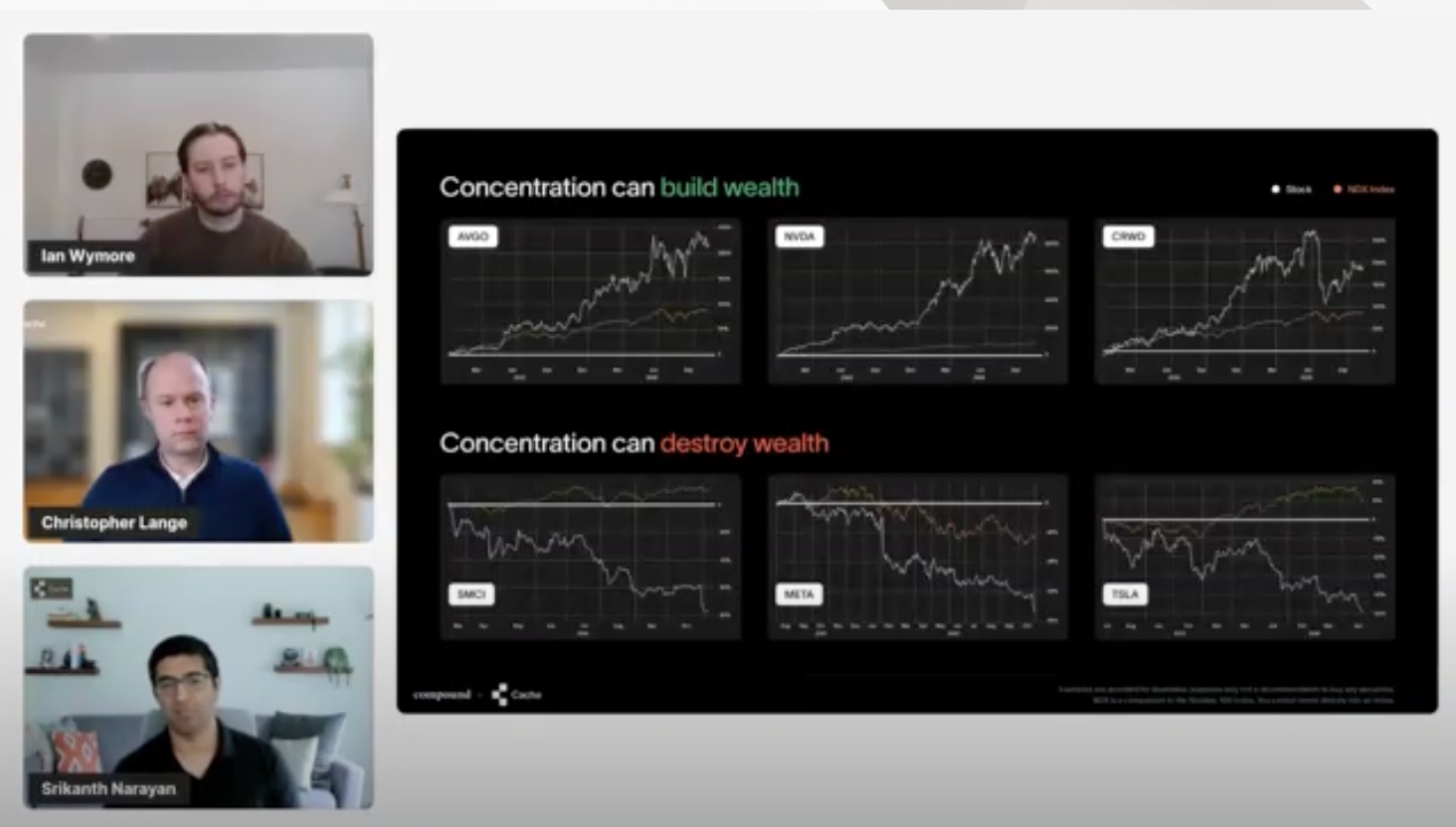

If most of your net worth is tied to a single company, that’s usually a sign of professional success. It can also be one of the fastest ways to lose what you’ve built.

Early on, stock concentration often works in your favor. Being focused on one company and one opportunity is how many people build meaningful wealth in the first place.

Over time, though, the math changes. Your equity (pre-IPO stock options or public RSUs) performs, you hold through the growth, and suddenly one position represents most of your wealth.

If you’re a current employee, that means the company also pays your salary — and suddenly your income, your equity, and your financial future all depend on the same single bet.

This is what can make your financial future fragile. Your wealth depends entirely on things you can’t control: market cycles, leadership decisions, regulatory shifts, competitive threats, or just a sudden shift in customer sentiment.

And yet, people often do nothing to diversify. Not because they don’t see the risk, but because the alternative feels worse: sell, trigger a massive tax bill, and potentially miss out on future gains. When the stakes are this high, doing nothing starts to feel like the safer bet.

Why It’s So Hard to Diversify a Concentrated Stock Position

Diversification isn't about winning. If you’re concentrated, you’ve likely already won. Diversification is about not losing.

The challenge is that reducing risk rarely feels good in the moment. Losses tend to feel more painful than equivalent gains feel rewarding.

Selling creates an immediate cost of taxes, potential upside, and a sense of finality. Holding preserves optionality, and the feeling that you’re avoiding regret, even as the risk continues to build.

A useful question to ask yourself: If you were given the same amount you have in equity as cash, would you reinvest all of it back into the same stock?

Most people wouldn’t. But that framing matters. It makes clear that holding isn’t avoiding a decision, it’s choosing to remain fully invested in one company, with all the same risks and consequences.

Key Takeaways:

- Concentration risk is real, and the impact on your finances is unpredictable.

- Diversification doesn't require choosing between "sell it all" or "hold it all." You can reduce risk gradually at a pace that feels sustainable.

- A personalized multi-year plan for stock diversification addresses both your financial and emotional needs.

What Happens When Most of Your Net Worth is Concentrated in One Company

Once upon a time, General Electric was one of the biggest companies in the world. Today, it isn't even in the top 50.

Now, imagine if a majority of your net worth had been tied to GE during that decline.

You might assume you’d sell if a stock started to fall. In reality, declines like GE’s don’t happen all at once. They unfold gradually, which makes impact feel manageable in the moment rather than urgent.

As the stock drifts lower, many people wait for a rebound. So selling the stock can feel premature — like locking in a loss — even as the risk quietly grows.

That hesitation is often compounded by emotion. If you’ve built your career at the company, your work and identity are tied to its success. Selling can feel less like a financial decision and more like a referendum on what you’ve built.

Separating those emotions from an already high-stakes financial decision is difficult. And that’s how paralysis sets in.

And this isn’t rare. When I speak to tech employees and executives seeking financial advice, roughly half of them have over 50% of their net worth concentrated in a single stock. Some have over 80% in one company.

It’s the kind of thing that can sneak up on you. Over time, you get paid in stock and you just hold onto it. Why? Well, the stock is seemingly doing well and you don’t have time to think about another strategy, so a high percentage of your entire net worth gets tied up in one place.

For example: Say your Coinbase equity jumps significantly in a single year. You've been selling gradually, but the spike creates both an opportunity and a problem: $7 million concentrated in one position, with a potential multi-million dollar tax bill if you sell.

Can you afford to sell?

Can you afford not to?

Executing a Strategic Multi-Year Diversification Plan

If you had $7M in cash, you probably wouldn’t invest all of it in a single stock. And yet, when that same $7M exists as equity, many people hesitate to act.

Selling can feel like giving something up: future upside or a long-held story about how wealth is built.

The reality is that there isn’t a single strategy that solves concentration risk. The best results usually come from layering multiple strategies at once — a plan that reduces risk steadily while managing taxes, liquidity needs, and emotions.

You can't eliminate a tax bill, but you can defer it for years — even decades — while you reduce your concentration risk. And while we don’t know which direction the stock or the market will swing, you’ll want to get a framework in place.

Below, we’ve outlined the steps high earners should take to evaluate their options and build a path forward.

Step 1: Understand the Risk You’re Actually Taking

Before making any diversification decisions, you need to know what concentration means for your life, not just your portfolio.

What happens if the stock drops 10%, 20%, or 50%?

Do your goals still look attainable? Does retirement get delayed? Does flexibility disappear?

Using modeling tools, like Compound’s Equity Simulator, you can make these market changes tangible instead of theoretical, and see how much of a decline you can absorb before it meaningfully affects your plan.

For example: The same decline has very different consequences depending on your stage of life. If you're 35 and still working, a 50% drop hurts but likely doesn't completely overhaul your financial plan. If you're 55 and just retired, that same drop can permanently change the trajectory of your finances.

When you decide what level of risk you’re comfortable with, you may find that, by your own metrics, some of your concentrated stock should live elsewhere.

Step 2: Add In Historical Market Context

You might be all-in on your company’s mission, product, and success — but market leadership changes dramatically over time, no matter how giant a company seems.

If you look at the top 10 biggest companies today, not many of them were on that list 10, 20, or 30 years ago. Over the course of a career, competitive landscapes shift, regulation changes, technology evolves, and leadership turns over.

The odds that any single company maintains top-tier performance for the rest of your career are fairly low. And you also have to consider the emotional bias that might make you overly confident in a single company’s success.

Step 3: Design a Flexible Plan That Works for You

There are many ways you can diversify: direct indexing for tax-loss harvesting, charitable giving, and Section 351 exchanges are just a few.

The right combination depends on your tax picture, cash flow needs, charitable intent, time horizon, and comfort with risk.

Plans should remain flexible. How you feel about the strategy you and your advisor put in place today may change over time. So it’s important to review your plan regularly and adjust as markets, tax law, and life circumstances evolve.

A simple way to think about strategy selection:

If your primary goal is tax deferral, and you can wait, exchange funds (typically a seven-year hold) or long-short investing (2-7 years) can be highly tax-efficient. These are best for high earners who've already maximized their charitable giving and don't need immediate liquidity.

If you need liquidity within 1-2 years, whether it’s for retirement, buying a house, or another large spending need, then gradual sales paired with direct indexing or loss-short investing for tax-loss harvesting keeps cash available and minimizes tax impact.

If you're charitably inclined, donor-advised funds, direct gifts of stock, or charitable trusts can reduce concentration while turning future giving into a current tax benefit.

If your main concern is downside protection, then derivatives (protective puts and covered calls) hedge risk while you wait to execute other strategies. That way, you can take more time to make decisions, and protect your wealth during volatile periods.

If you have a concentrated position but also sizable assets outside of that position, then Section 351 exchanges work well as part of the puzzle (limited to 25% of any single position and 50% of your top five positions). These work best for individuals who want to diversify part of their concentrated position immediately.

Of all these approaches, long-short investing provides significantly more flexibility — allowing full diversification in as little as 2-7 years without the exchange fund’s seven-year lockup or the 25% cap of Section 351 — to unwind a concentrated stock position in the shortest amount of time.

A hypothetical mix for diversifying stock concentration, for an individual whose six years from retirement with $8M+ in concentrated stock:

- 20% to charitable giving: Provides immediate tax deduction, satisfies philanthropic goals, and eliminates some concentration risk

- 30% to long-short strategy: Defers taxes while diversifying over three years, which balances tax efficiency with reasonably quick diversification

- 30% to gradual sales with tax-loss harvesting: Generates liquidity for near-term spending while providing control of when you sell and minimizing tax impact through offsetting losses

- 20% held with protective puts: Maintains some upside potential while providing downside protection

Note: Allocations are highly personalized, and will likely change and evolve with your financial goals and emotional considerations.

Diversification Strategies Glossary: How Each Approach Works

Direct Indexing for Tax-Loss Harvesting

A direct indexing strategy buys the underlying stocks of an index (like the S&P 500) individually. Even in positive market years, a meaningful portion of companies decline. That creates opportunities to harvest losses while maintaining market exposure.

You can work with your advisor to set loss-harvesting thresholds based on your individual tax situation.

Charitable Giving Strategies

When you gift appreciated stock directly to charity or contribute to a donor-advised fund (DAF), you get an immediate tax deduction for the full fair market value, the charity pays no capital gains tax, and you reduce concentration.

For example: A $1M gift in stock with a $200,000 cost basis could save you from paying $200,000+ in capital gains and would give you a $1M tax deduction. Donor-advised funds are flexible — you get an immediate deduction, but can distribute to specific charities over time.

Additionally, using charitable remainder trusts (you get income for a set period, and charity gets the rest) or charitable lead trusts (charity gets the income now, and you or your heirs get the rest later), can help you achieve your charitable goals and reduce stock concentration.

Charitable remainder trusts are particularly beneficial for pre-retirees who want an income stream as they support charity and defer taxes.

Derivatives and Options

Set up protective puts (automatic selling if the stock drops below a certain number) and covered calls (automatic selling if it rises above a certain number) to define your range of outcomes and have downside protection. A typical protective put might cost 2-4% annually; covered calls could generate 3-6% in premium income, but cap your upside at the strike price.

Keep in mind: options involve risk, and aren’t right for everyone.

Exchange Funds

With exchange funds, you can contribute stock into a vehicle where it's pooled with other investors' concentrated positions. You hold onto it for seven years, then receive a fully diversified portfolio without triggering any capital gains tax. These funds work best for those who can afford the wait and want maximum tax efficiency.

Section 351 Exchanges

This is a relatively new strategy that’s available for well-qualified advisors: You contribute stock into a partnership with other investors, and receive a diversified portfolio back within days. However, you can only contribute up to 25% of a single position, so this always works best as one piece of a broader strategy.

Long-Short Investing (Flex SMA)

You give your concentrated position to a specialized manager who sells portions immediately and uses the proceeds to short other positions and employ margin. Your $100 contribution, for example, might create $140-$250 of total market exposure depending on how much borrowing you’re comfortable with.

Over 2-7 years, the manager generates offsetting losses by selling underperforming holdings they've purchased (long positions) and strategically betting against certain stocks (shorting). These losses cancel out the gains from selling your concentrated shares, letting you diversify without immediate tax liability. This strategy solves both the exchange fund's seven-year wait and the 351 exchange's 25% limitation.

Reducing Risk, Deferring Taxes, and Gaining Peace of Mind

The benefits of diversifying go far beyond spreadsheets and tax forms.

Yes, strategic layering minimizes your tax bill — charitable giving provides immediate deductions, tax-loss harvesting offsets gains from necessary sales, and long-short strategies or exchange funds defer realization entirely. Charitable strategies can also deliver a rare triple benefit: saving on taxes, supporting causes you care about, and reducing concentration risk.

But the most meaningful shift is often psychological.

Large swings in a single stock can create uncertainty that’s hard to ignore. By building a strategic diversification plan that’s custom-fit to your financial picture, you can minimize worry and focus on living your life.

That peace of mind comes from having a clear framework: you know where you're going and how you'll get there. The plan stays flexible, but your financial independence no longer depends on short-term market moves or a single outcome.

Concentration helped build your wealth. Now it's time to protect it.

Investors often find more confidence when their financial independence isn’t too closely tied to one stock’s rise.

See your concentration risk in real-time. Try the Compound dashboard to visualize how much of your net worth depends on one position.

FAQs

How long does it typically take to diversify a concentrated stock position?

There's no specific timeline — it depends on your strategy mix and goals. Some approaches work immediately, while others take longer but offer better tax efficiency. Most people use a combination of strategies executed over 3-5 years. Your timeline should align with your life stage.

Won't I miss out on gains if I diversify and my company's stock keeps rising?

Potentially, but you need to shift your mindset. The potential for maximum gains comes with the risk of devastating losses. Strategic diversification isn't about eliminating all exposure, it’s about reducing the risk that a single outcome determines your entire financial future.

Can I really defer taxes for years while diversifying, or will I eventually pay the same amount?

You will likely pay capital gains eventually, but deferral has huge benefits. First, spreading the tax bill over multiple years can keep you in lower tax brackets. Second, strategies like tax-loss harvesting from direct indexing can offset gains, reducing your total tax burden. Third, some approaches can significantly reduce or even eliminate portions of the tax liability. Plus, your time is valuable — paying taxes in 5-7 years instead of today means that money stays invested and compounds for you, not the government.