Primer on Private Equity

TL;DR: Private equity (“PE”) generally refers to equity investments in private companies (we explore private debt here). Investors seek equity interests in private companies in different ways. In this explanation, we’ll go deeper on more traditional private equity investments in companies with more maturity as opposed to venture capital. We explore venture capital in greater depth here.

The vast majority of investors, approximately 85%, are only able to invest in public equity (stocks). Higher net worth individuals have the option to invest in the equity of private companies as well, significantly expanding one’s investable universe.

PE investors acquire equity interests in private companies with the intention of adding value to the business. Value-add initiatives include a number of different strategies such as mergers and acquisitions, operational improvements, increased capital expenditure, and cost cutting.

Companies that private equity firms invest in are then positioned for an exit via an IPO, sale to a corporation (strategic buyer), or sale to another private equity firm (financial buyer).

Historically, PE has performed better than public markets. According to Cambridge, PE has generated an annualized return of 12.1% over the past 25 years, compared with 9.1% for the S&P 500. However, PE investment requires selecting the right managers, paying high fees, and locking up your capital for a decade or more.

So what is private equity?

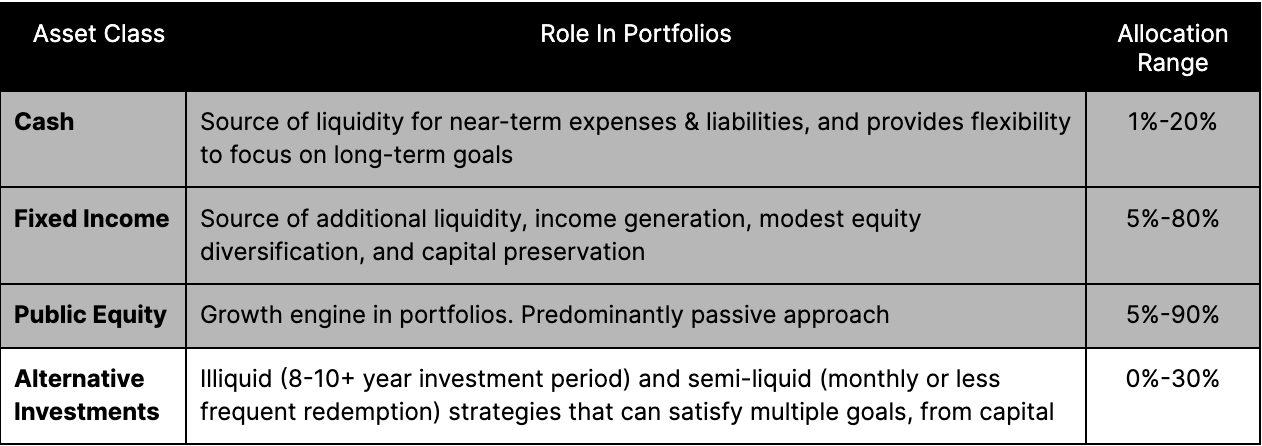

In the simplest terms, it’s just an asset class and a key component of how we build portfolios (see the framework below).

There are many flavors of PE, but they all share the underlying investment strategy of acquiring ownership in private companies that have reasonable prospects of offering an exit strategy (some larger funds will take public companies private). Publicly-traded companies represent only a small fraction of all investment opportunities. According to Blackrock, the vast majority of companies with more than $100 million in revenue are privately held, approximately 81%.

In contrast to public markets, where passive investing is a viable and often preferred option, accessing private companies requires specialization and a degree of active management, which means higher costs.

So where does PE’s “outperformance” come from? In private equity, investors usually play important and active roles in the management of a portfolio company and don’t just provide capital.

Imagine a 30+ year old family-run manufacturing business that has been successful. The CEO and founder wants to retire, but wants the business to outlive her. The company is too small to IPO, the founder doesn't want to sell to a competitor (they often can pay more than PE funds because of synergies), and so she hires a banker to help sell the business. A PE firm wins the deal to buy a majority stake in the company. The PE firm implements more efficient supply-chain management software, poaches an experienced leader from a competitor to run part of the organization, and provides capital and support in purchasing a few smaller competitors. Following these initiatives, the company’s profit margins and scale have improved such that they are now a candidate for an IPO at a much higher valuation.

In addition to value-add initiatives, some of the outperformance can be attributed to the illiquidity premium. Investors need to be compensated for taking additional risk with additional returns and illiquidity is a form of risk. Therefore, we would expect private, illiquid investments to outperform public, liquid investments.

Why invest in private equity?

For qualified investors with the assets, investment objectives, risk tolerances, and liquidity horizons appropriate for PE, there are a number of advantages to investing:

- Historically, PE is one of the best performing asset classes available to investors, with the potential to outperform public markets over the long term. Factors in PE’s strong performance include less competition, value-add from skilled managers, and illiquidity premiums for locking up capital.

- PE can provide diversification benefits, especially for investors with concentrated exposure in public equities. Although some PE strategies only invest in technology businesses, there are many other firms that maintain a broader focus to include business services, industrial, consumer, healthcare, etc.

- Investments in PE provide access to a different set of companies than traditional public-market investing. By sticking to public markets an investor is effectively ignoring a large slice of the market where there may be high return opportunities.

- Top performing PE managers can add material value to portfolio companies, increasing the return potential for investors. Skilled PE managers will improve portfolio companies through strategic guidance, acquisitions, and other initiatives that are less viable for public market investors.

- PE investments’ value may be less volatile than public equities during turbulent financial markets. PE investors’ control over portfolio companies means they can position their investments for potential downturns. Investments are also naturally long term and managers may delay exits for better market conditions. Volatile market conditions may provide PE managers opportunities to make investments at depressed valuations and position companies for success once markets recover.

What are the different types of private equity?

We mentioned above that there are different flavors of private equity, so let’s dig in:

Buyout strategies are common and are what typically comes to mind when referring to PE. In most cases, buyout strategies refer specifically to Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs). In an LBO transaction, the investor acquires a company utilizing a combination of equity (the PE investment) and debt (provided via a bank loan, different investment fund, or by a related party). Buyout transactions can provide excellent returns due to the comparatively small equity investment required to acquire the company. However, as with any leveraged investment, there is a heightened risk associated with taking on additional debt.

A positive outcome: In 2007, Blackstone purchased Hilton Hotels for $26 billion. Blackstone funded the purchase with $5.6 billion of equity (the PE investment) and $20.5 billion of debt (the leverage). The transaction took the publicly-traded company private, with shares being acquired at a 40% premium to public market pricing (not all LBOs target public companies). Blackstone successfully turned around the business and brought it public again in 2013, with Blackstone’s equity stake being valued at approximately $15 billion. The firm ultimately exited its position in multiple transactions through 2018 for a profit of almost $10 billion.

A pretty good outcome for Blackstone and its investors. However, in the interest of being balanced, let’s take a look at a transaction that did not go so well.

A negative example: KKR, TPG Capital, and Goldman Sachs acquired Energy Future Holdings (“EFH”) in 2007 for $45 billion – one of the largest LBOs in history. EFH is a Texas-based electric utility company that primarily generates power through coal power plants. The buyer’s thesis was that while temporarily lower natural gas prices had hurt EFH, making its power comparatively expensive, this trend would soon reverse. Unfortunately, the opposite occurred as natural gas prices continued to fall, making EFH’s coal power plants even less competitive. In 2014, EFH filed for bankruptcy. It’s safe to say our PE investors experienced major losses on the transaction. Even famed investor Warren Buffet reportedly lost approximately $900 million on the transaction where he supplied $2 billion of debt.

Growth equity strategies refer to investments in quickly growing companies that may be a candidate for IPO or sale. This is also sometimes referred to as late-stage venture capital investment. Growth equity investors typically make a minority investment and do not have the same control over a company compared to buyout strategies. Investors should be aware that growth equity investments are often in technology companies and will not provide much diversification for tech-concentrated investors. That being said, non-tech businesses do need growth capital to scale. Firms like General Atlantic or Silver Lake are big names in this space.

Distressed investment strategies consist of investments in struggling companies. The selected companies are frequently unprofitable or close to bankruptcy. Managers may invest via debt or equity, seeking to turn around companies and achieve great upside if successful. Distressed investment strategies typically have a longer time horizon and greater risk compared to other PE strategies. These strategies are also likely to originate from an initial debt investment, and so this straddles the world of private credit.

Outside of the different types, we can further segment private equity strategies by geography, sector, size, concentration, and more.

How should you invest in private equity?

Private equity structures normally include Limited Partners (“LPs”) and General Partners (“GPs”). The simplest way to think about both roles is that the LPs are the investors in the fund and the GPs are the managers of the fund. LP liability is limited to the amount they invest in the fund. GPs control the fund, do the work on the investments, benefit from any fees, and assume full liability for the activities of the fund.

There are a number of ways to gain exposure to private equity transactions. What is appropriate for you will depend on a number of factors, including your net worth and need for liquidity.

Traditional PE funds are drawdown, lockup structures that are typical to many forms of alternative investment (such as venture capital or private credit). Investors commit capital for the fund manager to draw down over time for PE transactions. These structures generally are illiquid for 10 years or more. It requires a significant amount of capital to diversify investments in traditional PE funds. Investment minimums can range from a few hundred thousand dollars to tens of millions.

Evergreen PE funds are a relatively new option that offers exposure to PE with the added potential for liquidity sooner. They may also be available to investors with a lower net worth requirement and investment minimum. These funds invest in some combination of direct transactions (usually minority investments without control), secondaries (purchasing existing interests in private equity funds or transactions), and primaries (investments in PE funds). It’s important to note that this liquidity is not guaranteed and there is an inherent risk to putting illiquid PE investments in a liquid structure. Investors rely on fund managers to provide consistent liquidity and avoid forced selling.

Fund of funds offer access to a number of private equity managers via one investment. The fund of funds manager will invest across a number of underlying PE funds. This investment structure may offer access to managers that may be difficult to invest in directly and allow diversification through one investment. Fund of funds can be attractive to investors with less capital to commit across potential deals. A primary downside with fund of fund structures is that investors pay two levels of fees, both at the fund of fund level and on the underlying funds. For example, a fund of fund may charge a 1% management fee and 10% performance fee in addition to the 2% management fee and 20% performance fee charged by each underlying fund manager.

Direct transactions refer to making investments in PE style transactions on a one-off basis. For most investors, this means participating alongside a private equity manager on a specific transaction (also sometimes called a co-investment). Direct transaction investors can diligence and underwrite specific investments on a deal-by-deal basis, only selecting transactions they believe in and that match their investment objectives. Additionally, direct transactions generally have lower fees compared to the other structures listed here or no fees at all. This investment structure requires high expertise to evaluate deals and a high amount of capital to get access and diversify among transactions. It’s also important to pay attention to the manager's motivation to open the transaction to outside investors.

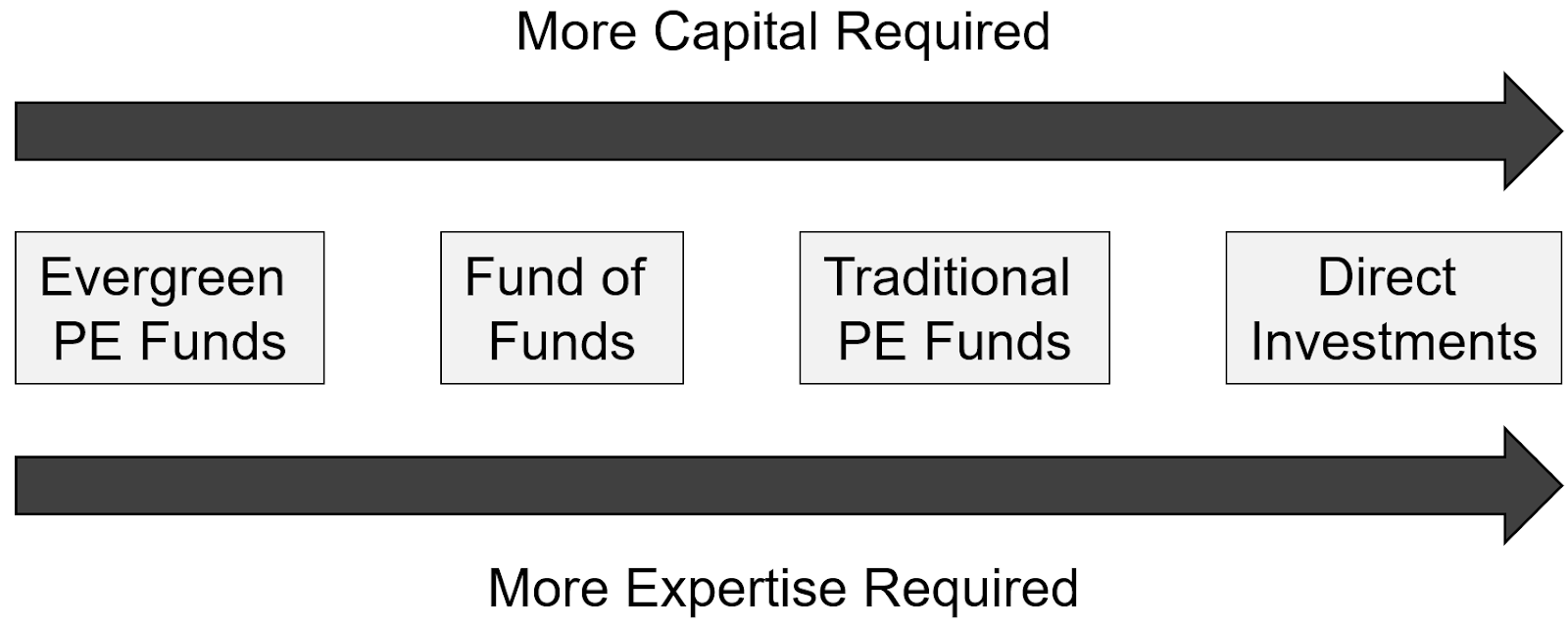

The below graphic shows PE structures by approximate investor expertise and capital required. Keep in mind this is a rough approximation and characteristics of structures will vary greatly by the individual investment.

What are the risks and downsides of private equity investing?

PE investing has a number of risks investors should be aware of before adding the asset class to their portfolio.

- Most PE investments are illiquid for a period of 10 years or more. While illiquidity can drive higher returns, investors need to be certain they will not need to access committed capital for a long period of time. A PE fund will sell its companies at varying intervals over that ten year period, but it can take 6-8 years to get your invested capital back, and then 8+ years to earn your return.

- Investments in private equity may be illiquid and difficult to value, and the value of these investments may fluctuate based on a variety of factors. Private equity investments may be subject to restrictions on transfer, which could limit the ability to sell these investments or require the investor to hold the investment for an extended period of time. The lack of a liquid market for these investments may make it difficult to determine their fair value, and valuations may be subject to a greater degree of uncertainty than those for publicly traded securities. In addition, the valuation of private equity investments may be affected by changes in the financial performance of the underlying companies, changes in market conditions, and other factors that may be difficult to predict or control. As a result, investors in private equity may experience significant fluctuations in the value of their investments, which may result in a loss of some or all of their investment. It is important for investors to carefully consider these risks before investing in private equity and to consult with their financial advisors to determine if such investments are appropriate for their investment objectives and risk tolerance.

- Successful execution of a PE strategy relies on utilizing significant leverage. Adding leverage to an investment amplifies both upside and downside potential. We are also in a higher interest rate environment than anytime in the last 15 years. Track records of funds previously benefited from the low interest environment, moving forward funds may struggle to achieve similar returns in a high interest rate environment.

- PE investments are naturally risky even with talented managers. Investments in smaller companies may have greater potential for failure and binary outcomes.

- Investments in PE provide a reduced level of transparency compared with public market investments. Investors must trust managers to be good stewards of capital, provide accurate information, and responsibly value portfolio positions.

- PE investment returns may appear more uncorrelated and lower risk than they actually are. Investors rely on PE returns to increase diversification of their portfolios from public markets and potentially reduce overall portfolio risk. However, PE strategies can be reliant on IPO markets or M&A activity to achieve exits, which is heavily correlated with public markets. In addition, PE investments may display lower standard deviations that are not accurate due to valuations only occurring periodically and managers being reluctant to mark down positions.

- PE fees can reduce the benefits of PE investment. Typical structures include a 2% management fee and 20% performance fee. PE investments need to outperform public market investments to some extent to make up for higher fees. Adding on fund expenses means the outperformance of PE can be less impactful on a net returns basis.

- Additional tax and operational complexities. When investing in a drawdown structured private equity fund, your tax filing process inherently becomes more complicated. The vast majority of private equity funds issue K-1s and may require you to file multiple states. This likely increases the cost of your annual tax filings, and given that K-1’s can be delayed, may require you file extensions. Finally, drawdown structures means you’ll invest in increments over time, where the fund will call capital and you’ll be required to wire or transfer funds with ~2 weeks notice. The penalty for missing a capital call varies, but requires active monitoring and administration.

The bottom line

PE can provide higher return potential and portfolio diversification benefits for investors with the necessary net worth and ability to lock up capital. PE investors benefit from inefficient markets where active management can add more value. Many strategies will make investments in earlier stage companies with more potential for exponential growth and valuation expansion. Decisions on access structures, size of fund, and sector focus will be heavily dependent on individual investors’ investment objectives and broader portfolios.

Investors should be aware of fees and risks associated with PE investment. However, for high net worth investors with the necessary sophistication, PE can be a great addition to a balanced asset allocation.

If you’re interested in learning more about Compound’s investment management approach, book a time here with an advisor.